It's Thanksgiving! But before we give thanks and tuck in, let's talk history.

How did Thanksgiving become such an integral part of America's identity? We dug up five useful classroom resources to help you and your students get to the bottom of that question:

1. The Smithsonian Asks: Where Did Your Favorite Thanksgiving Day Food Originate?

Did you know most of the ingredients used in contemporary Thanksgiving spreads came from Mexico and South America? Even turkey, which is typically associated to North American fare, got its start south of the border.

Did you know most of the ingredients used in contemporary Thanksgiving spreads came from Mexico and South America? Even turkey, which is typically associated to North American fare, got its start south of the border.

Experts believe the turkey was domesticated roughly 2,000 years ago in both Mexico and the Midwestern U.S., though it was the Mexican turkey that endured and eventually made the epic journey to our Thanksgiving table. Thanks to the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, you can learn about the origins of almost all your Thanksgiving grub (image via Science Magazine).

2. George Washington and Thanksgiving

Mount Vernon has amazing primary sources dedicated to the history and legacy of George Washington, including his iconic 1789 Thanksgiving Proclamation - essential reading for both Thanksgiving and general US history buffs alike.

Mount Vernon has amazing primary sources dedicated to the history and legacy of George Washington, including his iconic 1789 Thanksgiving Proclamation - essential reading for both Thanksgiving and general US history buffs alike.

It's like the Thanksgiving blueprint, including the first iteration of the holiday's date (Washington announced November 26, 1789, as the official day of Thanksgiving, though we'll get to the changing of the date later on).

It also inspired Abraham Lincoln’s 1863 Thanksgiving Proclamation, which he issued on the same day as Washington's, October 3, as tribute.

Though Thanksgiving wasn't legally recognized as a public holiday until 1941, Washington's Proclamation certainly set the wheels in motion for not only Thanksgiving but also the many U.S. public holidays that followed (image via Mount Vernon website).

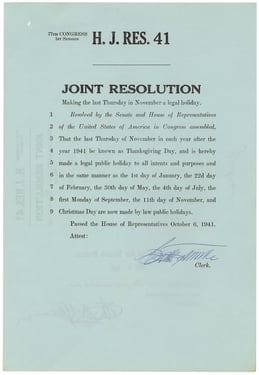

3. Here's how Congress officially established Thanksgiving

Thanks to George Washington, November 26, 1789, was the first "Day of Publick Thanksgivin" under the new Constitution, but in the years and Presidencies that followed the date varied. President Lincoln's 1863 Proclamation cemented Thanksgiving on the last Thursday of November, but that became an issue in 1939, when November's last Thursday fell on the last day of the month. The US was still recovering from the Great Depression at this point and, with the Second World War looming, President Roosevelt issued a Proclamation moving Thanksgiving one week earlier to ensure a longer Holiday shopping period. But only 32 states adhered to the Proclamation, so for two years the country celebrated Thanksgiving on two different Thursdays!

Thanksgiving was reunified in 1941, when the House and the Senate agreed on a joint resolution establishing the fourth Thursday of every November as the official Thanksgiving holiday. That way, everyone could have their cake - or pumpkin pie - and eat it... even when there are five Thursdays in November. It's all detailed in these primary sources courtesy of the National Archives.

4. Thanksgiving and African American history

When we discuss US history - or any historical discourse, for that matter - it's critical we look at it from every angle. Thanksgiving in the context of African American history is particularly intriguing: how does a holiday devoted to giving thanks fit in to a community that's been systematically disenfranchised if not enslaved for generations?

When we discuss US history - or any historical discourse, for that matter - it's critical we look at it from every angle. Thanksgiving in the context of African American history is particularly intriguing: how does a holiday devoted to giving thanks fit in to a community that's been systematically disenfranchised if not enslaved for generations?

The African American Registry (AAREG) has fascinating primary source material on this subject. This brief article covers the early years of Thanksgiving in the African American community, both during slavery and immediately following the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863. Did you know, for example, that slaves would often plot their escapes around Thanksgiving, when slave-owners were distracted by the harvest? Post-emancipation, Thanksgiving became a largely church-based holiday for African Americans, a time to strengthen their community and increase their voice against ongoing racial injustice (image courtesy of the AAREG).

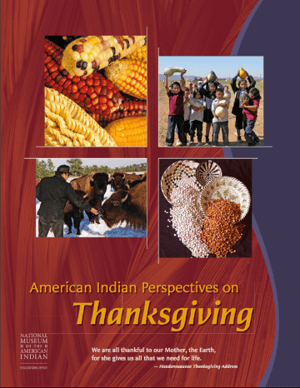

5. Indigenous Perspectives on Thanksgiving

Much like the AAREG resource above, you simply can't discuss Thanksgiving without considering another systematically disenfranchised group in US history: the First Nations. Once you strip away our contemporary Thanksgiving tropes - the football games, the Black Friday deals - and get right down to the very roots of this holiday, we owe most of our Thanksgiving values to the people who lived here first.

Much like the AAREG resource above, you simply can't discuss Thanksgiving without considering another systematically disenfranchised group in US history: the First Nations. Once you strip away our contemporary Thanksgiving tropes - the football games, the Black Friday deals - and get right down to the very roots of this holiday, we owe most of our Thanksgiving values to the people who lived here first.

We already discussed how the Thanksgiving table is heavily influenced by indigenous crops and staples, but there are broader, more spiritual elements at play here too. The Founding Fathers weren't strangers to the notion of 'giving thanks', as this was commonplace in Christian prayer, but the more animist elements of the holiday - the concept of humbling yourself to the natural generosity and grandeur of the land - was largely a First Nations ethos that lives on to this day. We found this amazing classroom resource courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian, which dives deep into their take on Thanksgiving - past, present and future. The PDF document includes suggested classroom activities and discussion topics. It's really amazing!